The first word that comes to mind when I look at the works of Anna Tuori is restless. There are restless “walkers” populating her paintings, ready to go but also wanting to stay. A restless hand made the paintings, moving over the surface, adding scribbles and patches in different places. And the resulting works never rest; they appear active, vibrant, and alive.

The Walkers is a series of paintings that Tuori started in 2017. Having seen them in different situations, I started wondering why they work so well. At first, they look quite simple in composition and casual in execution. There is a human figure whose head has been chopped, cut by the frame of the painting. Yet the figure is not entirely headless: a face turns up at another, rather unexpected place, for instance between the legs, or on the jacket of the walker. This series makes me think about movement, about having or lacking direction as a human being, and about grace and speed. But these works also evoke contrasts between burden and lightness, roughness and delicacy. They are open figures rather than specific characters, which enables us to identify with them. The longer I look, the more details appear on the surface and the more sophisticated the paintings become, in terms of having nuance of expression and balance in composition. The individual paintings cannot be grasped all at once, each as an overall image. Only through time, through putting together the pieces that are spread over the painting, does the scene become a whole in the mind of the beholder.

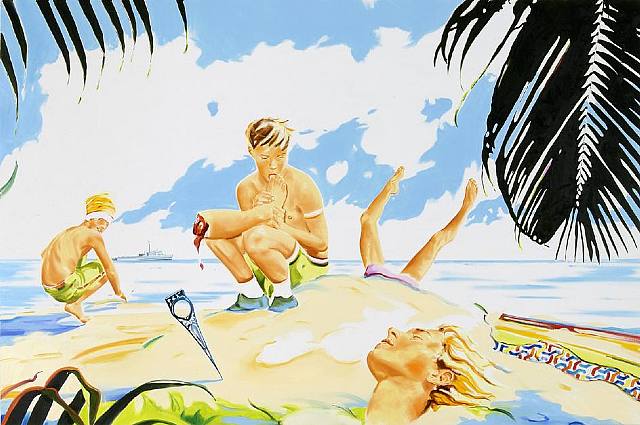

Painting is, among other things, about looking and seeing. For that reason, it seems quite relevant that the walking figures are not looking at us. We don’t meet their gaze; we are looking at a moving person from an outsider’s perspective. For Tuori, reflections on the impact of seeing have a special place in the works she made for her Paris exhibition. This goes for the Walkers, but also for the different portraits of women that are on display in the show. In Dissociation (2019), there is a face with many eyes, or actually multiple faces within one figure. In Off on an Adventure (2019), the facial expression usually accentuated through eyes, mouth, and nose is almost absent, hidden under light paint. In the details of the figures, a lot can be noticed, about eyes for example, but also about how hair falls, how an arm is lifted. Just like in daily life, in the way people look and move, a lot is happening and can be read as an indication of somebody’s well-being. A gaze can be unpleasant, experienced as offensive or even as an act of aggression, while looking can also transmit love or care. In the dense traffic of looks, flirts, or meaningful gazes, Tuori seems very alert and redirects the sight lines to where she thinks it is necessary. The women in her works are certainly not just there to be pretty and admired. They are complicated, hard to read, or hiding behind smoke. They seem independent from what beholders might want to see in them.

The way Tuori paints the portraits looks like drawing with the brush – sketch-like, with energetic lines. Despite the restlessness of the figures, or even their neuroses or anxieties, there is generally an upbeat quality to the work. There is pleasure in the drama that unfolds. The artist seems to enjoy the whole range of expression that is possible in painting, as well as the ability to loosen things up through lines. She doesn’t feel like an expressionist, though, instead mixing an expressive gesture with other things. “In the painting, emotional or intuitive and conscious or intellectual approaches do not exclude each other. Just like expressive or conceptual ways do not exclude each other,” the artist commented.

During a dinner in Helsinki with the artist and some friends, we spoke about the fact that Finland was listed as the happiest country in the world for two years in a row, according to a United Nations study. How do you measure happiness? Apart from economic indicators such as gross domestic product, aspects like life expectancy, corruption in government, and the ways communities interact with each other were included. The locals at the dinner table made jokes about Finnish happiness, knowing that the long, dark winters do not exactly bring out the cheer in people. Yet I could also detect joy in the ironic self-reflections. Similarly, in Tuori’s paintings, there is a mocking, light touch, while at the same time nothing less than the struggle of life is what we are looking at. And this light note comes not just from being Finnish, but also from painting, from the transformative power that painting has over life.

Tuori’s mentality behind painting is not one that gets too comfortable with itself. The artist has changed and developed her approach over the years. It started from a dialogue with a romantic conception of art. The figures in some older paintings create their own imaginary world as a hideout. Tuori was shaped by modern ideals as well, by belief in progress, and the confidence that we can design our own lives. In the recent works, I sense a reluctance to tell too much of a story, and the artist also doesn’t lead us to wander around in an imagined, painted world. There is a rougher edge to the work, and less usage of effect to impress. Painting now seems to spring from the wish to balance believing and being skeptical, being empathetic and not caring so much what others might think. You just need to be alert, open, and flexible. Tuori’s figures appear to be in a permanent process of loosening up. They are as restless as I could hope for.

–Jurriaan Benschop

This text was published in the catalog of the exhibition Anna Tuori ‘Never seen a Bag Exploding,’ scheduled to be on view till 2 May 2020 (but currently closed because of covid19 restrictions). For information and obtaining the catalog contact Suzanne Tarasieve Gallery in Paris